Tarsila do Amaral (1886 - 1973)

Tarsila do Amaral was one of the most significant figures in Brazilian art, an icon of the Modernist movement in Brazil, and a key force in creating a visual identity for national art. Her work profoundly influenced Brazilian modern art, particularly alongside Anita Malfatti, with whom she led the consolidation of the first phase of Brazilian Modernism. The painting Abaporu (1928), one of her most iconic works, inspired the creation of the Anthropophagic Movement, founded by Oswald de Andrade, her husband at the time. This work was a turning point in Brazilian art, marking a historical moment for the country’s artistic modernity.

Tarsila’s relationships with other major artists, such as Candido Portinari, Di Cavalcanti, and José Pancetti, also highlight her historical importance. Her biography, complemented by a vast body of literature and studies on her work, has made her one of the most documented and researched figures in the history of Brazilian modern art.

During the 1920s—a culturally vibrant period in both Brazil and France—Tarsila do Amaral pursued her artistic formation in Paris, where she studied under renowned masters such as Emile Renard at the Académie Julian, and with André Lhote, Albert Gleizes, and Fernand Léger. This European experience was crucial to the development of her style, which over time fused elements of industrial modernity from both France and Brazil. Although she engaged with artists like Pablo Picasso and other figures of European Modernism, Tarsila followed a unique path, maintaining a creative independence that set her apart.

Tarsila’s painting is characterized by an exuberant use of vibrant colors, often inspired by her childhood memories in Capivari, São Paulo’s interior. Her visual approach, with intense colors and elements referencing both rural and modern Brazil, reflects her quest for a singular visual representation of the country, avoiding the simplification of her work as merely “rural.” On the contrary, her art traverses multiple influences, forming a cosmopolitan and multifaceted portrait of her reality and her time.

Tarsila do Amaral was born on September 1, 1886, at Fazenda São Bernardo in Capivari. She came from a wealthy family connected to the São Paulo coffee cycle, and her childhood was shaped by a conservative and patriarchal environment. From an early age, Tarsila was educated to be cultured and multilingual, with initial training that included piano, embroidery, reading, French, and extensive access to her father’s library. She studied at Colégio Nossa Senhora de Sion in São Paulo and completed her education at Colégio Sacré-Coeur de Jésus in Barcelona. Her first painting, Tharcilla (documented in the Catalogue Raisonné Tarsila do Amaral, Vol. 1), marked the beginning of her artistic journey.

In 1906, Tarsila married her cousin André Teixeira Pinto, but the marriage faced challenges due to the conservatism of the era. The couple had a daughter, Dulce, but the marriage was short-lived. After the separation, Tarsila returned to the family farm with her daughter.

In 1916, Tarsila began studying sculpture with William Zadig and Mantovani. The following year, she took up painting with Pedro Alexandrino Borges and later with George Fischer Elpons. In 1920, encouraged by João de Souza Lima, she went to Paris, studying at the Académie Julian and with the Cubists André Lhote and Albert Gleizes, while also engaging with major European and Brazilian artists, including Pablo Picasso and Heitor Villa-Lobos. Tarsila became an important figure in the European art scene, fostering a cultural exchange between Brazil and Europe.

In 1922, her painting Passaporte was accepted at the Salon Officiel des Artistes Français, consolidating her international artistic presence. During this period, she grew close to figures like Di Cavalcanti and Oswald de Andrade, with whom she formed the Grupo dos Cinco, a cornerstone of Brazilian Modernism. Tarsila participated in the famed Semana de Arte Moderna in 1922 and, in 1923, traveled through Europe with Oswald de Andrade. During this time, she deepened her engagement with Cubism and met artists such as Fernand Léger, whose influence is evident in her work.

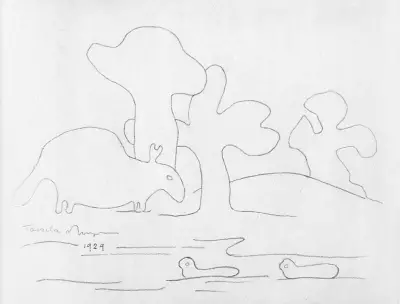

From 1924, Tarsila entered a new phase, described as the “rediscovery of Brazil.” This Pau-Brasil period was marked by the use of vivid colors and the exploration of distinctly Brazilian themes, such as native fauna and flora, addressed through a modern and original visual language. In this phase, Tarsila immortalized Brazil’s exuberance through her vibrant colors and “national animals.”

In 1928, the painting Abaporu became a milestone in her career, inspiring the Anthropophagic Movement conceived by Oswald de Andrade. The work, whose name comes from the Tupi-Guarani language meaning “man who eats human flesh,” symbolized the idea that Brazil should “devour” and reinterpret foreign cultural influences in its own creative way. This manifesto not only gave rise to the movement but also became a landmark in Brazil’s cultural identity.

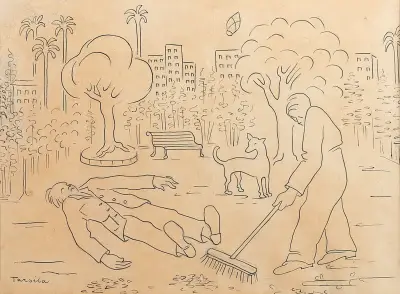

The 1929 economic crisis deeply affected Tarsila, who lost her farm and assets, like many other Brazilians. In 1930, she faced the end of her marriage with Oswald de Andrade, who later married Patrícia Galvão, known as Pagú. Yet Tarsila did not withdraw from art. During this period, she worked as a curator at the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo and began organizing the museum’s collection catalog. She also faced political challenges, being accused of subversion due to her involvement with leftist ideas.

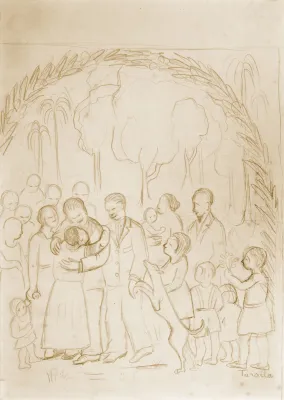

In 1931, Tarsila traveled with her second husband, the psychiatrist Osório César, to the Soviet Union. This trip was a turning point in her art, leading her to produce works with strong social critique. Her engagement with workers and the laboring class became prominent, with the painting Operários emerging as a symbol of this phase. Tarsila became increasingly involved with social issues, incorporating the struggles of workers into her canvases.

In the following years, Tarsila faced personal challenges, including an unsuccessful surgery and the loss of her daughter Dulce. Despite hardships, she continued her artistic production, embraced Spiritism, and donated works to charitable causes.

At 80, in 1969, Tarsila had a major retrospective titled Tarsila, 50 Years of Painting, exhibited at MAM-RJ and MAC-SP. She passed away on January 17, 1973, leaving an undeniable legacy and a body of work essential for understanding modern Brazilian art.

Her innovative style and ability to connect Brazil with international artistic currents established Tarsila do Amaral as one of the foremost figures in Brazilian art. Her work continues to inspire and be studied, cementing her as a central pillar of Modernism in Brazil.

Interviews

Veja Magazine (02/23/1972) - Leo Gilson Ribeiro

Veja: You were in Europe during the Semana. Even so, you are considered one of its key figures. Why is that?

Tarsila: Although I was in Europe, I think I participated in the Semana de 22 through a letter that Anita Malfatti sent me, describing everything in detail. Now I don’t even know where that letter ended up. I was astonished by what she told me and by Monteiro Lobato’s harshness when he spoke about her, without understanding anything, very reactionary. Imagine, he thought of himself as a painter, Monteiro Lobato! I was very impressed—what is this thing? Anita was rightfully hurt, as Monteiro Lobato described her paintings as if they were done by a donkey with a brush tied to its tail, swatting at flies, producing random strokes on the canvas, you see?

Veja: But the Semana…

Tarsila: Just before leaving for Europe, I rented my studio to a German professor, Professor Elpons, the only Impressionist in Brazil. He was the only one who gave me exposure to Impressionist works, because nothing arrived here except through Professor Pedro Alexandrino, who had spent twenty years in Paris and knew all the major painters. Many said it was a waste of time to work in Pedro Alexandrino’s studio, calling him old-fashioned; but he was well-prepared, and in retrospect, it certainly wasn’t a waste of time.

Veja: How did you discover your talent?

Tarsila: I began working in São Paulo under Pedro Alexandrino’s guidance. It did me no harm to see that his approach was traditional, academic, with the old method of copying in fusain to exercise the hand. I even did the head of a black man; he wanted me to have a steady hand, giving me large sheets of paper to work on. He explained everything—how to draw freehand, without rulers. I started with drawing; I was not a colorist at first. I also copied plaster casts, shaded forms, anatomical studies, learning proportions thoroughly. He worked at the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios and brought models, which was excellent for understanding anatomy and correct proportions.

Veja: Was São Paulo very provincial in the arts?

Tarsila: Oh yes, the general taste was for landscapes identical to life, and still lifes—the glimmer of metal reproduced on canvas, so realistic! That phase was not harmful to me; it was preparatory. When I arrived in Europe, I went straight to the Académie Julian, studying nudes in a large studio. I took my works: a pastel old man’s head, then an oil painting of a Dutch woman, and a charcoal study of a black man. There were many studios, and the fashion was nudes—the model posed only five minutes for rapid sketches. I liked that, as I already had practice. Later, I studied with a prominent hors-concours professor, who held exhibitions and admired my work. I forget his name now, but he drew attention to what I was doing, saying: “Voyez ce qu'elle fait, comme c’est puissant!” (Look at what she does, how powerful it is!). I returned to Brazil shortly after the Semana, but I did not appreciate what Anita Malfatti was doing; it was all very distorted. Of course, I was completely opposed to Monteiro Lobato. Later that year, Anita studied with Pedro Alexandrino too, because her mother, very traditional, opposed her daughter’s innovations, claiming they were worthless. Anita was disheartened by her mother’s anger—it was terrible!

Veja: Did you find a hostile environment upon your return?

Tarsila: I arrived in early June, traveling by ship, which lacked the convenience of airplanes—Gago Coutinho would cross the Atlantic soon after. But the sea voyage was so peaceful! These were Royal Mail ships, the best. Later, France launched the Lutèce and the Marsilia. No, I didn’t find the environment hostile. I received many people, poets, in my studio on Rua Vitória, which belonged to my family.

Veja: You were a very beautiful woman…

Tarsila: Who? Me? Well, naturally, I was younger then, better than today. That’s when I met Oswald de Andrade, who was very extravagant, spoke ill of everyone, and when he found something amusing, he had to say it even if it offended friends, sacrificing everything for a bon mot. Once Paulo Prado quarreled with him and never spoke again, even though Paulo had written an excellent preface for Oswald’s book Pau-Brasil, published in Paris. When Oswald had something to say, he couldn’t resist. He made a comment about Dona Veridiana Prado, implying she was not fully “Aryan,” calling her a glorious mulata. Paulo Prado was a close relative, so he never spoke to Oswald again.

Veja: Did he also quarrel with Mário de Andrade?

Tarsila: Yes. Later he missed him and asked me to write a letter to Mário. Oswald was very temperamental; I wrote it, but Mário replied it was impossible—Oswald had offended him too much, he was deeply resentful. With me, it was different; Mário had always been my friend. When Oswald saw Mário would not reconcile, he continued speaking ill of him. It was a pity, considering the seriousness of his work. I did all the illustrations for his books.

Veja: Did the famous Aba-Puru start from there?

Tarsila: No, I wanted to make a painting that would astonish Oswald, something truly unusual. That led to Aba-Puru. I didn’t know why I wanted to do it… later I discovered. Aba-Puru is that monstrous figure you know—the small head, thin arm resting on the elbow, enormous long legs, with a cactus resembling both a sun and a flower. When Oswald saw it, he was terrified and asked: “What is this? Extraordinary!” He immediately called Raul Bopp to see it. Bopp came to my studio on Rua Barão de Piracicaba, a beautiful house my father had recently bought. He was also astonished, and Oswald said: “It’s like something savage, wild.” I wanted a wild name too. Using a dictionary by Montoia, a Jesuit priest, I found “Abá” for man and “Puru” for a human-eating man—so Aba-Puru it became.

Veja: So, you were the origin of the Anthropophagic Movement?

Tarsila: Raul Bopp thought we should build a movement around this painting. He found it unusual and wrote a fascinating book on indigenous Amazonian languages. People began to claim Oswald created Aba-Puru and the Anthropophagic Movement. He didn’t mind; he found it amusing.

Veja: That’s why he dated documents from the year the Indians ate Bishop Sardinha in Bahia?

Tarsila: Yes, they launched the Anthropophagy Movement, and every Wednesday Chateaubriand offered a page in his newspaper to the movement. Geraldo Ferraz, known as “the butcher,” spoke about art—it was fitting, since anthropophagy meant eating flesh. He explained it to the readers. But because of irreverence towards families subscribing to Diário de São Paulo, Chateaubriand eventually asked them to stop, fearing he would lose subscribers.

Veja: Aba-Puru, with its monstrous deformed figure, seems like a nightmare.

Tarsila: Funny you say that—I like inventing forms I’ve never seen, but I didn’t know why I made Aba-Puru that way. I asked myself: How did I do this? A friend married to the mayor said: “Whenever I see Aba-Puru, I remember childhood nightmares.” I then realized it was a psychic memory from when we were children on the farm. After dinner, the servants would tell ghost stories, claiming limbs would fall from the ceiling. Perhaps Aba-Puru reflects those memories.

Veja: Just as the Anthropophagic Movement drew from indigenous and African cultures, did Fernand Léger, with his themes of machines, factories, and modern society, influence your painting?

Tarsila: I admired his work greatly and was friends with him, but I didn’t attend his studio. I was also friends with his wife. Later, rumors said he designed earrings for me—imagine! My inspiration came from São Paulo itself, from industrial society. What I did was novel in Brazil then. I was so well-received that the state government bought one of my large works, now in Campos do Jordão, depicting a factory. During my Rio exhibition, a friend from Pernambuco sent me all the press clippings about Aba-Puru. There were incredible inventions; they claimed my studio was like Renoir’s, full of nudes, with divans covered in purple velvet scattered everywhere. I was even compared to Anita Malfatti. At that time, a journalist wrote that Oswald de Andrade hadn’t even married me yet! I became a tourist attraction in São Paulo. My marriage to Oswald was a luxury event, attended by President Washington Luís. They spoke of my many loves and even called me a trendsetter. Naturally, every time I returned from Europe, I brought novelties. Once, I wore a beautiful checkered silk dress with puffed sleeves and wide blue bows for the vernissage at my studio on Rua Barão de Itapetininga. I welcomed visitors cordially, unaware that many had razors in their pockets, ready to destroy my works. But seeing me in that dress, they were taken aback and could not carry out their plan.

Tell me: Did you grow up in São Paulo city or in the countryside?

Tarsila: When I was little, I lived on a farm. My father loved everything about farms; he bought many lands. He was a very wealthy man because his father was also well-known in São Paulo genealogy as José Estanislau do Amaral, "the Millionaire." He started with nothing, producing castor oil, with one or two slaves helping him. Then he gradually improved, buying farms, selling coffee in Santos, making a considerable profit. I was raised in the countryside, and I think that’s why I remain so strong even at my age. In an arm-wrestling match (shows her arm), even men have a hard time beating me, you know?

And does this strength of the land, the countryside, appear in your painting as well?

Tarsila: Exactly. You know, as a child on the farm, I saw my mother surrounded by many church saints. I already loved painting and made my first, crude copies of the saints. I painted Saint Francis Xavier when I was about four. I adored drawing and being around chickens, chicks, and I drew everything I saw. Then I received a white kitten as a gift, which I loved—it was named Falena. She had many mates, and I ended up with forty cats around me, meowing, there on the Capivari farm. I also spent time at the São Bernardo farm, which my father had already purchased by then. It was a very large and beautiful house, and it was there, looking at the letters on the entrance gate, that I learned to read. The letters were almost the size of this cabinet here. My mother taught me: “Look, this is a B, it’s called B; here is an A,” and I immediately remembered the shapes. I didn’t even feel I was being taught to read before starting school. I also made dolls from plants: plants with square stems that bloomed, which I turned into little sculptures, making arms and legs to play with. I grew up on this farm, and when my father learned that a Belgian family had settled nearby—the noble Van Harenberg Val-mont family, with an eighteen-year-old daughter—he sent to ask if she could teach us French. She came but taught us nothing; it was my mother who taught her Portuguese. I learned French because my father wanted his children to be very educated. Later, we went to Europe, and no French person ever suspected I wasn’t French—they always said I spoke completely without a foreign accent, you know?

In Paris, were you in contact with Picasso, Apollinaire, Breton?

Tarsila: Ah, yes. Cocteau was also a close friend. I hosted many Brazilian lunches at my Paris atelier, which Paulo Prado discovered had once been Cézanne’s atelier, on Rue Moreau, in a not very desirable neighborhood, but it was so hard to find a studio in Paris! Many American and foreign artists were there, and space was scarce. Mine was on the fifth floor; you had to climb all the stairs, no bathroom, very primitive—actual baths were only at the public bath. Vila-Lobos came often, and Cocteau too. They even said Cocteau was a very good musician. Vila-Lobos improvised on a grand piano in my studio, and Cocteau would grimace, saying: Non, ça n’est pas quelque chose de neuf! (No, that’s nothing new!). Then Vila-Lobos would play something else, and Cocteau would shake his head: No, not original. He even sat under the piano claiming it was pour mieux entendre (to hear better), but never approved Vila-Lobos’ music—the Brazilian folklore was déjà entendu (already heard) for him. You can imagine the quarrels, with Vila-Lobos exuberant and flamboyant… It was a climate of constant debate, with differing literary, political, and aesthetic positions creating perpetual confusion.

You’ve had such a rich life; when were you happiest?

Tarsila: That was when my father bought a mansion on Rua Barão de Piracicaba, because my mother loved a very large house. It was there that I hosted parties, dinners, and had two young men, fifteen or sixteen, as waiters. I installed an excellent wine cellar, unmatched in São Paulo, selected piece by piece by a French sommelier, with the name of a known artist—I don’t remember now, Maurice Chevalier? No, it was Charles Boyer, I think, a film actor, wasn’t it?

Where do you find so much strength to live? A fall left you bedridden most of the day. Recently, you lost your only daughter. Soon after, your only granddaughter drowned. Are you religious?

Tarsila: Oh yes, I am. I am very devoted to the Infant Jesus of Prague, as I received many graces through prayers to him. It’s a miraculous novena—I know it by heart: "Oh Jesus, who said: Ask and you shall receive, seek and you shall find, knock and the door will be opened." When I read it, I shivered imagining that door opening… This inspired a painting of the Child Jesus with a black child, symbolizing the humble, along with Japanese and Indigenous figures, which I gifted to a priest running an orphanage. I also copied sacred oleographs…

Portinari also began by copying saints.

Tarsila: Ah, I was disappointed with Portinari when I met a Cubism scholar in Paris and studied with him for over six months. I don’t think Portinari knew how to paint cubist works. For example, he intended to do Tiradentes. He drew it with brush and ink, then glued pieces of paper over the drawing—that was never Cubism!

Besides religious sentiment, there’s also a tone of memory in your paintings…

Tarsila: One of my most successful works in Europe was called A Negra. I have memories of an old slave woman I knew when I was five or six—slaves living on our farm. She had drooping lips and large breasts because, I was told, at the time black women would tie stones to their breasts to elongate them while carrying children on their backs. In a painting I made for São Paulo’s IV Centenary, I created a procession with a black woman in the background and a baroque church, a recollection of that woman from my childhood, I think. I invent everything in my painting. What I see or feel—a beautiful sunset or this black woman—I stylize.

Your painting, so poetic, is then a tender evocation of a happy childhood?

Tarsila: I think you’re not far from the truth.

Almanaque Abril

Tarsila do Amaral, (b. September 1, 1886, Fazenda São Bernardo, Capivari, São Paulo – d. January 17, 1973, São Paulo).

Critical Commentary

"Rio de Janeiro will discover Tarsila and will experience, through this discovery, a sense of marvelous enchantment. Tarsila is the greatest Brazilian painter. None before her reached that plastic strength—admirable in invention and execution—that she alone possesses among us" (...) "Nor has anyone captured the wildness of our land so well, the barbaric man each of us is, us true Brazilians consuming, with all possible ferocity, the imported culture, the worthless old art, all the prejudices through which the West, via the ruses of catechism, poisoned our sensibilities and thinking."

Oswald de Andrade

ANDRADE, Oswald. [Originally published in an interview by Oswald de Andrade to O Paiz, 1929]. In: AMARAL, Aracy. Tarsila: sua obra e seu tempo. 3rd rev. ed. São Paulo: Edusp: Editora 34, 2003. p. 314

"Tarsila’s Pau-Brasil and Anthropophagic phases are undoubtedly the highlights of her career as a painter and key to her place in Brazilian art history. They synthesize, plastically, her genuine relationship with the land, and her pictoriality, as Haroldo de Campos noted, updated through contact with Cubism, allowed her 'to extract this lesson not from things but from relationships, enabling her to read the structure of Brazilian visuality. Reducing everything to a few simple basic elements, establishing new and unforeseen relationships within the syntax of the painting, Tarsila encoded our environmental and human landscape in a cubist key while rediscovering Brazil through this selective and critical (yet loving and lyrical) reinterpretation of the essential structures of a visuality that surrounded her since childhood.' (...)".

Aracy Amaral

AMARAL, Aracy. Tarsila: sua obra e seu tempo. São Paulo: Perspectiva: EDUSP, 1975. (Estudos, 33).

"Through her attitude and work, especially in the 1920s and ’30s, Brazil is rediscovered after centuries of alienation and submissive absorption of metropolitan models. With her, Brazil and the world engage equally and creatively. To Cubism’s angular geometry, she added sinuous, enveloping rhythms of a more tropicalized Baroque tradition; she also blended recovered themes, iconography, and colors from genuinely popular manifestations with the self-acquired refinement of technique, aiming never at formal naïveté, even while occasionally evoking the childlike fantasy of Henri Rousseau or the near-caricature humor characteristic of early modernist irreverence.

In Tarsila’s painting, the universal becomes particular, the popular merges with the learned, maturity revisits childhood. What was initially foreign becomes ours, integrated consciously into our national identity, re-experiencing it as if for the first time."

Roberto Pontual

PONTUAL, Roberto. Tarsila do Amaral. In: _______. Arte brasileira contemporânea: Coleção Gilberto Chateaubriand. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Jornal do Brasil, 1976. p. 75.

"Tarsila’s relationship with Léger’s work shows her intelligence in analyzing French art. What she absorbed from Léger was the use of the machine motif. Yet the metaphor Léger develops addresses industrial society. Tarsila made 'Brazilianness' her distinctive trait, adopting the 'machine language' (as Oswald de Andrade used telegraphic language) to situate Brazil’s perception in the context of industrialization. The machine in her work is not merely a present reference but an attempt to grasp the Brazilian symbolic universe through a contemporary lens. Formally, this approach distanced Tarsila from a servile imitation of Léger. In his work, colors—mostly primary or metallic—seek maximum contrast, reflecting urban life. His drawing follows his painting, using light and dark to suggest volume, as a preparation for the canvas. Tarsila’s drawing, however, functions more as a note, using line to reveal the defining structure of the object. The stroke flows smoothly, building the object while organizing the paper’s surface."

Carlos Zílio

ZÍLIO, Carlos. A querela do Brasil: A questão da identidade da arte brasileira: a obra de Tarsila, Di Cavalcanti e Portinari, 1922-1945. Rio de Janeiro, Relume-Dumará, 2nd ed., 1997.

"All in all, the greatest strength of Tarsila’s painting is also the source of its striking fragility—here lies a discrepant surface (Eiffel Tower + Carnival in Madureira, as seen in one of her paintings…), held on a razor’s edge, full of gaps, articulating countless polarities. Truth be told, even in the artist’s most admirable works, one can witness the formal challenges she tackles to handle modern vocabulary with ease: the paintings often oscillate between an almost naturalistic depiction of ethnic types and regional landscape peculiarities, and a more assertive geometrization of forms, responding to modern art’s demand for constructive clarity.

We must recognize that, due to this dual approach (aiming to embrace both the world and her native village), many details in her painting verge on the picturesque: Tarsila cleverly bends the logic of Cubism, which would advise reducing the human figure to the anonymous types of urban civilization, and instead delights in detail. She, for instance, experiments with a dozen different ways to paint hands and feet, which, as one can see, is almost a sentimental indulgence for someone aspiring to (some) generalization of form and a structural perception of pictorial space.

(...) to speak of incompleteness and incongruity in Tarsila’s work may also be to speculate on a specific mode of poetic productivity in Brazilian art, which, as her painting reveals, was driven as much by the constructive discipline learned from modern art as by its opposite: the inclination toward a tábula rasa, to jumble everything, to relativize the excessive and already normative weight of a given influence, recombine, and seek new cultural syntheses."

Sônia Salzstein

SALZSTEIN, Sônia. A saga moderna de Tarsila. In: TARSILA, anos 20. Org. Sônia Salzstein. Textos de Aracy Amaral et al. São Paulo: Galeria de Arte do Sesi: Página Viva, 1997. p.13, p.16.

Testimonies

"I found in Minas the colors I loved as a child. Later, I was told they were ugly and rustic. I followed the trail of refined taste… But then I took my revenge on this oppression by putting them on my canvases: pure blue, violet-tinged pink, bright yellow, singing green, all in gradations more or less strong depending on the mix with white. Above all, clean painting, fearless of conventional canons. Freedom and sincerity, a certain stylization that adapted to the modern era. Clear contours, giving a perfect impression of the distance between one object and another."

Tarsila do Amaral

AMARAL, Tarsila. Pintura Pau Brasil e Antropofagia.

In: Revista Anual do Salão de Maio. São Paulo, nº 1, 1939.

Magazine edited by Flávio de Carvalho.

"Abstractionism, whose principles aim—or should aim—entirely at the intellect, no longer moves me today. I once supported it in 1923, when I studied with Albert Gleizes the 'integral Cubism,' whose essence corresponds perfectly with abstractionism.

All calculated, weights and counterweights, equilibrium, conventional dynamism, lines and colors varying to infinity, but always lines and colors.

After a while, one begins to desire escape from this artistic eternity, which addresses only the intellect, and to return to the sentimental, the human, since in the human complex the senses also have their rights."

Tarsila do Amaral

GOTLIB, Nádia Battella. Tarsila do Amaral, a modernista.

São Paulo, Editora Senac São Paulo, 1998, p. 77.

Characteristics of her work

Use of vivid colors: Tarsila was a modernist; she painted Brazil, disregarded the rules of traditional painting, and filled her canvases with color, lots of color. Tarsila successfully translated all the shades of a country into vibrant hues.

Cubist influence (use of geometric forms).

Exploration of social themes, daily life, and Brazilian landscapes.

Non-standard aesthetics (surrealist influence during the Anthropophagic phase).

Main works by Tarsila

Pátio com Coração de Jesus (Ilha de Wright) - 1921

A Espanhola (Paquita) - 1922

Chapéu Azul - 1922

Margaridas de Mário de Andrade - 1922

Árvore - 1922

O Passaporte (Portrait de femme) - 1922

Retrato de Oswald de Andrade - 1922

Retrato de Mário de Andrade - 1922

Estudo (Nu) - 1923

Manteau Rouge - 1923

Rio de Janeiro - 1923

A Negra - 1923

Caipirinha - 1923

Estudo (La Tasse) - 1923

Figura em Azul (Fundo com laranjas) - 1923

Natureza-morta com relógios - 1923

O Modelo - 1923

Pont Neuf - 1923

Rio de Janeiro - 1923

Retrato azul (Sérgio Milliet) - 1923

Retrato de Oswald de Andrade - 1923

Autorretrato - 1924

São Paulo (Gazo) - 1924

A Cuca - 1924

São Paulo - 1924

São Paulo (Gazo) - 1924

A Feira I - 1924

Morro da Favela - 1924

Carnaval em Madureira - 1924

Anjos - 1924

EFCB (Estrada de Ferro Central do Brasil) - 1924

O Pescador - 1925

A Família - 1925

Vendedor de Frutas - 1925

Paisagem com Touro I - 1925

A Gare - 1925

O Mamoeiro - 1925

A Feira II - 1925

Lagoa Santa - 1925

Palmeiras - 1925

Romance - 1925

Sagrado Coração de Jesus I - 1926

Religião Brasileira I - 1927

Manacá - 1927

Pastoral - 1927

A Boneca - 1928

O Sono - 1928

O Lago - 1928

Calmaria I - 1928

Distância - 1928

O Sapo - 1928

O Touro - 1928

O Ovo (Urutu) - 1928

A Lua - 1928

Abaporu - 1928

Cartão Postal - 1928

Antropofagia - 1929

Calmaria II - 1929

Cidade (A Rua) - 1929

Floresta - 1929

Sol Poente - 1929

Idílio - 1929

Distância - 1929

Retrato do Padre Bento - 1931

Operários - 1933

Segunda Classe - 1933

Crianças (Orfanato) - 1935/1949

Costureiras - 1936/1950

Altar (Reza) - 1939

O Casamento - 1940

Procissão - 1941

Terra - 1943

Primavera - 1946

Estratosfera - 1947

Praia - 1947

Fazenda - 1950

Porto I - 1953

Procissão (Panel) - 1954

Batizado de Macunaíma - 1956

A Metrópole - 1958

Passagem de nível III - 1965

Porto II - 1966

Religião Brasileira IV – 1970

Meaning of the Paintings

Blue Hat: This painting was created after Tarsila attended Emile Renard’s studio. Works from this period are characterized by great softness and a lyrical atmosphere.

Self-Portrait or Manteau Rouge: In Paris, Tarsila attended a dinner honoring Santos Dumont wearing this stunning cape (Manteau Rouge, in French, means red coat or mantle). Beyond its beauty, she wore very elegant and exotic clothing, and her presence was striking wherever she went. After this dinner, she painted this remarkable self-portrait.

The Black Woman: This painting was executed by Tarsila in Paris while studying with Fernand Léger. Léger was so impressed that he showed it to all his students, declaring it an exceptional work. In The Black Woman, we see Cubist elements in the background, and the piece is also considered a precursor to the Anthropophagy movement in Tarsila’s painting. This black woman with large breasts reflects part of Tarsila’s childhood, as her father was a wealthy landowner and black women, often daughters of former slaves, acted as amas-secas, a type of nanny who cared for the children.

EFCB (Central Railroad Station of Brazil): This painting was created after a trip to Minas Gerais with the modernist group. It was during this period that Tarsila began the painting entitled Pau-Brasil, with distinctly Brazilian themes and colors. This work was produced for a modernist exhibition-lecture organized by the poet Blaise Cendrars in São Paulo in June 1924.

Carnival in Madureira: Tarsila returned from Paris and spent the 1924 Carnival in Rio de Janeiro. Interestingly, she included the iconic Eiffel Tower amidst the Carioca favela.

A Cuca: Tarsila painted this piece in early 1924 and wrote to her daughter that she was creating “very Brazilian” paintings, describing the subject as “a strange creature in the countryside, with a frog, an armadillo, and another invented animal.” This painting is also considered a precursor to Anthropophagy in Tarsila’s work and was donated by her to the Musée de Grenoble in France.

The Fisherman: This painting features exceptional color and depicts a distinctly Brazilian theme: a fisherman on a lake within a small village surrounded by typical vegetation. It was exhibited in Moscow, Russia, in 1931 and acquired by the Russian government.

Brazilian Religion: Once, upon returning from Europe, Tarsila arrived at the port of Santos and went to buy homemade sweets in a humble fisherman's home. Inside, she noticed a small altar adorned with little saints, decorated with vases and crepe-paper flowers. She found it so picturesque that she painted this wonderful work.

Manacá: A beautiful painting with vibrant colors. Tarsila represents this flower in a way that is distinctly her own.

Abaporu: This is the most important painting ever produced in Brazil. Tarsila created it as a gift for the writer Oswald de Andrade, her husband at the time. When he saw the painting, he was astonished and called his friend, the writer Raul Bopp. They stared at the strange figure and felt it represented something exceptional. Tarsila then recalled her Tupi-Guarani dictionary, and they named the painting Abaporu (the man who eats). This inspired Oswald to write the Manifesto Antropófago and launch the Anthropophagic Movement, aimed at “devouring” European culture and transforming it into something distinctly Brazilian. Despite its radical nature, the movement was crucial for Brazilian art and represented a synthesis of the Brazilian Modernist movement, which sought to modernize the nation’s culture in a uniquely Brazilian way. Abaporu remains the most expensive Brazilian painting ever sold, reaching US$1,500,000, purchased by Argentine collector Eduardo Costantini.

The Lake: A magnificent painting from the Anthropophagic phase, featuring the vibrant colors and themes typical of Tarsila. Her nephew Sérgio purchased it and kept it for many years.

The Egg or Urutu: This painting contains key symbols of Anthropophagy. The large snake is a creature that evokes fear and possesses a “devouring” power. The egg represents genesis, the birth of something new—reflecting the essence of Anthropophagy. This work belongs to the important collection of Gilberto Chateaubriand and is frequently exhibited in major shows.

The Moon: This painting was Oswald de Andrade’s favorite, her husband at the time she painted it. He kept it until his death (even after separating from Tarsila).

Postcard: We see the beautiful city of Rio de Janeiro in this painting, considered the greatest postcard of Brazil. The monkey is an Anthropophagic creature of Tarsila, part of the composition.

Anthropophagy: In this painting, we see the fusion of Abaporu with The Black Woman, inverted from the original composition. It is one of Tarsila’s most significant works. Eduardo Costantini, the collector who owns Abaporu, is very interested in this piece and has offered a substantial sum for it, which was declined by the current owners.

Solo Exhibitions

1926 - Paris, France - Solo exhibition at Galerie Percier

1928 - Paris, France - Solo exhibition at Galerie Percier

1929 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - First solo exhibition in Brazil at the Palace Hotel

1931 - Moscow, Russia - Solo exhibition at the Museum of Western Modern Art

1933 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Tarsila do Amaral: Retrospective at the Palace Hotel

1936 - São Paulo, SP - Solo exhibition at Palácio das Arcadas

1950 - São Paulo, SP - Tarsila 1918-1950 at MAM/SP

1961 - São Paulo, SP - Solo exhibition at Casa do Artista Plástico

1967 - São Paulo, SP - Solo exhibition at Tema Galeria de Arte

1969 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Tarsila: 50 Years of Painting at MAM/RJ

1969 - São Paulo, SP - Tarsila: 50 Years of Painting at MAC/USP

1970 - Belo Horizonte, MG - Tarsila do Amaral at MAP

Group Exhibitions

1922 - Paris, France - Salon Officiel des Artistes Français

1922 - São Paulo, SP - 1st General Exhibition of Fine Arts at Palácio das Indústrias

1923 - Paris, France - Exhibition of Brazilian Artists at Maison de l'Amérique Latine

1926 - Paris, France - Salon des Indépendants

1928 - Paris, France - Salon des Indépendants

1929 - Paris, France - Salon des Surindépendants

1930 - New York, USA - The First Representative Collection of Paintings by Brazilian Artists at the International Art Center, Nicholas Roerich Museum

1930 - Recife, PE - Exposition de l'École de Paris

1930 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Exposition de l'École de Paris

1930 - São Paulo, SP - Exhibition at a Modernist House

1930 - São Paulo, SP - Exposition de l'École de Paris

1931 - Paris, France - Salon des Surindépendants

1931 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Revolutionary Salon at Enba

1931 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Exhibition at the First Modernist House of Rio de Janeiro, Rua Toneleros

1933 - São Paulo, SP - 1st Modern Art Exhibition of SPAM at Palacete Campinas

1934 - São Paulo, SP - 1st São Paulo Fine Arts Salon, Rua 11 de Agosto

1937 - São Paulo, SP - 1st May Salon at Esplanada Hotel

1938 - São Paulo, SP - 2nd May Salon at Esplanada Hotel

1939 - New York, USA - Latin American Art Exhibition at Riverside Museum

1939 - São Paulo, SP - 3rd May Salon at Galeria Itá

1941 - São Paulo, SP - 1st Art Salon at the National Industrial Fair, Parque da Água Branca

1944 - Belo Horizonte, MG - Modern Art Exhibition at Edifício Mariana

1944 - London, England - Exhibition of Modern Brazilian Paintings at the Royal Academy of Arts

1944 - Norwich, England - Exhibition of Modern Brazilian Paintings at Norwich Castle Museum

1944 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - North American and Brazilian Painters

1944 - São Paulo, SP - Brazilian-North American Modern Painting Exhibition at Galeria Prestes Maia

1945 - Bath, England - Exhibition of Modern Brazilian Paintings at Victory Art Gallery

1945 - Bristol, England - Exhibition of Modern Brazilian Paintings at Bristol City Museum & Art Gallery

1945 - Buenos Aires, Argentina - 20 Brazilian Artists at Salones Nacionales de Exposición

1945 - Edinburgh, Scotland - Exhibition of Modern Brazilian Paintings at National Gallery of Scotland

1945 - Glasgow, Scotland - Exhibition of Modern Brazilian Paintings at Kelvingrove Art Gallery

1945 - La Plata, Argentina - 20 Brazilian Artists at Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes

1945 - Manchester, England - Exhibition of Modern Brazilian Paintings at Manchester Art Gallery

1945 - Montevideo, Uruguay - 20 Brazilian Artists at Comisión Municipal de Cultura

1945 - Santiago, Chile - 20 Brazilian Artists at Salones Nacionales de Exposición, Universidad de Santiago

1946 - Santiago, Chile - Brazilian Contemporary Painting Exhibition at Universidad de Chile

1946 - Valparaíso, Chile - Brazilian Contemporary Painting Exhibition at Universidad de Chile

1947 - São Paulo, SP - Galeria Domus: Inaugural exhibition

1951 - São Paulo, SP - 1st São Paulo International Biennial at Pavilhão do Trianon – acquisition prize and 2nd national painting prize

1952 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Brazilian Artists Exhibition at MAM/RJ

1952 - Santiago, Chile - Exhibition of Contemporary Brazilian Painting, Drawings and Prints at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Universidad de Chile

1952 - São Paulo, SP - Commemorative Exhibition of the 1922 Modern Art Week at MAM/SP

1953 - São Paulo, SP - 2nd São Paulo International Biennial at Pavilhão dos Estados

1954 - São Paulo, SP - Contemporary Art: exhibition from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo at MAM/SP

1955 - Pittsburgh, USA - The 1955 Pittsburgh International Exhibition of Contemporary Painting, Department of Fine Arts, Carnegie Institute

1956 - São Paulo, SP - 50 Years of Brazilian Landscape at MAM/SP

1957 - Buenos Aires, Argentina - Modern Art in Brazil at Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes

1957 - Lima, Peru - Modern Art in Brazil at Museo de Arte de Lima

1957 - Rosario, Argentina - Modern Art in Brazil at Museo Municipal de Bellas Artes Juan B. Castagnino

1957 - Santiago, Chile - Modern Art in Brazil at Museo de Arte Contemporáneo

1959 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - 30 Years of Brazilian Art at Enba

1960 - São Paulo, SP - Women's Contribution to Visual Arts in the Country at MAM/SP

1962 - São Paulo, SP - Selection of Brazilian Artworks from the Ernesto Wolf Collection at MAM/SP

1963 - Campinas, SP - Contemporary Painting and Sculpture at Museu Carlos Gomes

1963 - São Paulo, SP - 7th São Paulo International Biennial at Fundação Bienal – special room

1964 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - The Nude in Contemporary Art at Galeria Ibeu Copacabana

1964 - Venice, Italy - 32nd Venice Biennale

1966 - Austin, USA - Art of Latin America since Independence at The University of Texas at Austin, Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery

1966 - New Haven, USA - Art of Latin America since Independence at Yale University Art Gallery

1966 - New Orleans, USA - Art of Latin America since Independence at Isaac Delgado Museum of Art

1966 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - Self-Portraits at Galeria Ibeu Copacabana

1966 - San Diego, USA - Art of Latin America since Independence at La Jolla Museum of Art

1966 - San Francisco, USA - Art of Latin America since Independence at San Francisco Art Museum

1966 - São Paulo, SP - Half a Century of New Art at MAC/USP

1966 - Belo Horizonte, MG - Traveling Exhibition of Works from the MAC/USP Collection at Museu de Arte da Prefeitura de Belo Horizonte

1966 - Curitiba, PR - Traveling Exhibition of Works from the MAC/USP Collection

1966 - Porto Alegre, RS - Traveling Exhibition of Works from the MAC/USP Collection at Museu de Arte do Rio Grande do Sul

1967 - New York, USA - Precursors of Modernism in Latin America at Inter American Art Center

1968 - São Paulo, SP - Tamagni Collection at MAM/SP

1970 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ - 8th Resumo de Arte JB

1970 - São Paulo, SP - Inaugural Exhibition at Galeria Astréia

1972 - São Paulo, SP - 2nd International Print Exhibition at MAM/SP

1972 - São Paulo, SP - The Week of 22: Antecedents and Consequences at MASP

1972 - São Paulo, SP - Art/Brazil/Today: 50 Years Later at Galeria Collectio

Posthumous Exhibitions

1973 - São Paulo SP - 12th São Paulo International Biennial, Fundação Bienal - special room

1974 - São Paulo SP - Solo Exhibition, Galeria Raquel Arnaud Babenco and Mônica Filgueiras de Almeida

1974 - São Paulo SP - The Modernists’ Era, MASP

1975 - São Paulo SP - 13th São Paulo International Biennial, Fundação Bienal

1975 - São Paulo SP - SPAM and CAM Exhibition, Museu Lasar Segall

1975 - São Paulo SP - Modernism 1917–1930, Museu Lasar Segall

1976 - Paris (France) - Brazil: 20th Century Artists, Artcurial/Centre d'Art Plastique Contemporain

1976 - São Paulo SP - 20th Century Brazilian Art: Paths and Trends, Galeria de Arte Global

1976 - São Paulo SP - The Salons: Família Artística Paulista, Maio and the São Paulo Artists’ Union, Museu Lasar Segall

1976 - São Paulo SP - Brazilian Art: Figures and Movements, Galeria Arte Global

1978 - Belo Horizonte MG - Tarsila do Amaral, Galeria Guignard

1978 - São Paulo SP - Landscape in the Pinacoteca Collection: 19th Century to the 1940s, Pinacoteca do Estado

1979 - São Paulo SP - Drawings of the 1940s: Homage to Sérgio Milliet, Biblioteca Mário de Andrade

1979 - São Paulo SP - 15th São Paulo International Biennial, Fundação Bienal

1980 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Homage to Mário Pedrosa, Galeria Jean Boghici

1980 - Santiago (Chile) - 20 Brazilian Painters, Chilean Academy of Fine Arts

1980 - São Paulo SP - The Brazilian Landscape: 1650–1976, Paço das Artes

1981 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - From Modern to Contemporary: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, MAM/RJ

1982 - Lisbon (Portugal) - Brazil: 60 Years of Modern Art, Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, Centro de Arte Moderna José de Azeredo Perdigão

1982 - Lisbon (Portugal) - From Modern to Contemporary: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, Centro de Arte Moderna José de Azeredo Perdigão

1982 - London (UK) - Brazil: 60 Years of Modern Art, Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, Barbican Art Gallery

1982 - Penápolis SP - 5th Northwest Fine Arts Salon, Fundação Educacional de Penápolis, Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Penápolis

1982 - São Paulo SP - From Modernism to the Biennial, MAM/SP

1983 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Brazilian Self-Portraits, Galeria de Arte Banerj

1984 - Fortaleza CE - 7th National Fine Arts Salon

1984 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - 7th National Fine Arts Salon - Salon of '31, MAM/RJ

1984 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Salon of '31, Funarte

1984 - São Paulo SP - Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection: Portrait and Self-Portrait in Brazilian Art, MAM/SP

1984 - São Paulo SP - Masterworks, Studio José Duarte de Aguiar

1984 - São Paulo SP - Tradition and Rupture: Synthesis of Brazilian Art and Culture, Fundação Bienal

1985 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Drawings by Tarsila do Amaral, Acervo Galeria de Arte

1985 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Portrait of the Collector in His Collection, Galeria de Arte Banerj

1985 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Rio: Surrealist Tendencies, Galeria de Arte Banerj

1985 - São Paulo SP - Rio: Surrealist Tendencies, MAC/USP

1985 - Curitiba PR - Rio: Surrealist Tendencies, Museu Guido Viaro

1985 - Porto Alegre RS - Rio: Surrealist Tendencies, Museu de Arte do Rio Grande do Sul Ado Malagoli

1985 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Tarsila do Amaral: Drawings, Acervo Galeria de Arte

1985 - São Paulo SP - 100 Works Itaú, MASP

1985 - São Paulo SP - Solo Exhibition, Secretaria Municipal da Cultura, Departamento de Bibliotecas Públicas

1986 - Porto Alegre RS - Paths of Brazilian Drawing, MARGS - highlight room

1986 - São Paulo SP - Tarsila 1886–1986, MAC/USP

1987 - Indianapolis (USA) - Art of the Fantastic Latin America: 1920–1987, Indianapolis Museum of Art

1987 - New York (USA) - Art of the Fantastic Latin America: 1920–1987, Queens Museum

1987 - Paris (France) - Modernity: 20th Century Brazilian Art, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

1987 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - To the Collector: Homage to Gilberto Chateaubriand, MAM/RJ

1987 - São Paulo SP - 19th São Paulo International Biennial – Singular Imaginaries, Fundação Bienal

1987 - São Paulo SP - The Biennials in the MAC Collection: 1951–1985, MAC/USP

1987 - São Paulo SP - The Craft of Art: Painting, SESC

1987 - São Paulo SP - Tarsila: Drawings 1922–1952, Studio José Duarte de Aguiar and Ricardo Camargo

1988 - Mexico City (Mexico) - Art of the Fantastic Latin America: 1920–1987, Centro Cultural/Arte Contemporáneo

1988 - Miami (USA) - Art of the Fantastic Latin America: 1920–1987, Center for the Fine Arts

1988 - São Paulo SP - MAC 25 Years: Highlights from the Early Collection, Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo

1988 - São Paulo SP - Modernity: 20th Century Brazilian Art, MAM/SP

1989 - Lisbon (Portugal) - Six Decades of Brazilian Modern Art: Roberto Marinho Collection, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Centro de Arte Moderna José de Azeredo Perdigão

1989 - São Bernardo do Campo SP - Visions from the Edge of the Field, Marusan Galeria de Arte

1990 - São Paulo SP - The Municipal Art Collection of São Paulo, MASP

1991 - Stockholm (Sweden) - Viva Brasil Viva, Kulturhuset, Konstavdelningen and Liljevalchs Konsthall

1992 - Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Canary Islands) - Overseas, Art in Latin America and the Canaries 1910–1960, Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno

1992 - Madrid (Spain) - Overseas, Art in Latin America and the Canaries 1910–1960, Casa de América

1992 - Paris (France) - Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century, Centre Georges Pompidou

1992 - Poços de Caldas MG - Brazilian Modern Art: Collection of the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo, Casa da Cultura de Poços de Caldas

1992 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - 1st Towards Niterói: João Sattamini Collection, Paço Imperial

1992 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Nature: Four Centuries of Art in Brazil, CCBB

1992 - São Paulo SP - Sérgio’s View on Brazilian Art: Drawings and Paintings, Biblioteca Municipal Mário de Andrade

1992 - São Paulo SP - The Formation of the Modernist Eye, MAC/USP

1992 - Seville (Spain) - Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century, Estación Plaza de Armas

1992 - Zurich (Switzerland) - Brasilien: Entdeckung und Selbstentdeckung, Kunsthaus

1993 - Cologne (Germany) - Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century, Kunsthalle Cologne

1993 - New York (USA) - Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century, MoMA

1993 - Poços de Caldas MG - Mário de Andrade Collection: Modernism in 50 Works on Paper, Casa da Cultura de Poços de Caldas

1993 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Brazil, 100 Years of Modern Art, MNBA

1993 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Emblems of the Body: The Nude in Brazilian Modern Art, CCBB

1993 - São Paulo SP - 100 Masterpieces from the Mário de Andrade Collection: Painting and Sculpture, IEB/USP

1993 - São Paulo SP - Brazilian Art in the World: A Trajectory, 24 Brazilian Artists, Dan Galeria

1993 - São Paulo SP - Modern Drawing in Brazil: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, Galeria de Arte do Sesi

1993 - São Paulo SP - Modernism in the Museum of Brazilian Art: Painting, MAB/FAAP

1993 - São Paulo SP - Always Tarsila, Rua Guararapes, 78

1994 - Poços de Caldas MG - Unibanco Collection: Commemorative Exhibition for 70 Years of Unibanco, Casa da Cultura de Poços de Caldas

1994 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Modern Drawing in Brazil: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, MAM/RJ

1994 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Trenches: Art and Politics in Brazil, MAM/RJ

1994 - São Paulo SP - The Modernist Adventure: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection from MAM/RJ, Galeria de Arte do Sesi

1994 - São Paulo SP - Brazilian Modern Art: Selection from the Roberto Marinho Collection, MASP

1994 - São Paulo SP - Brazil 20th Century Biennial, Fundação Bienal

1995 - Brasília DF - Brasília Collections, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Palácio do Itamaraty

1995 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Unibanco Collection: Commemorative Exhibition for 70 Years of Unibanco, MAM/RJ

1995 - São Paulo SP - Parisian Modernism of the 1920s: Experiences and Encounters, MAC/USP

1996 - São Paulo SP - Brazilian Art: 50 Years in the MAC/USP Collection 1920–1970, MAC/USP

1996 - São Paulo SP - Ex Libris/Home Page, Paço das Artes

1996 - São Paulo SP - Figure and Landscape in the MAM Collection: Homage to Volpi, MAM/SP

1996 - São Paulo SP - Women Artists in the MAC Collection, MAC/USP

1997 - Barcelona (Spain) - Tarsila, Frida, Amélia: Tarsila do Amaral, Frida Kahlo, Amélia Peláez, Centro Cultural de la Fundación la Caixa

1997 - Barra Mansa RJ - The Museum Visits the Gallery, Centro Universitário de Barra Mansa

1997 - Madrid (Spain) - Tarsila, Frida, Amélia: Tarsila do Amaral, Frida Kahlo, Amélia Peláez, Sala de Exposiciones de la Fundación la Caixa

1997 - São Paulo SP - Anthropophagic Appropriations, Itaú Cultural

1997 - São Paulo SP - Mário de Andrade and the Modernist Group, Centro Cultural e de Estudos Aúthos Paganos

1997 - São Paulo SP - Tarsila 1920s, Galeria de Arte do Sesi

1998 - Brasília DF - A Brazilian Like Me, Like Who?, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

1998 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Constantini Collection at the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, MAM/RJ

1998 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Negotiated Images: Portraits of the Brazilian Elite, CCBB

1998 - São Paulo SP - 24th São Paulo International Biennial - Historical Core: Anthropophagy and Cannibalism Stories, Fundação Bienal

1998 - São Paulo SP - Constantini Collection at MAM, MAM/SP

1998 - São Paulo SP - MAM Bahia Collection: Paintings, MAM/SP

1998 - São Paulo SP - Highlights from the Unibanco Collection, Instituto Moreira Salles

1998 - São Paulo SP - The Collector, MAM/SP

1998 - São Paulo SP - Modern and Contemporary in Brazilian Art: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection - MAM/RJ, MASP

1999 - Porto Alegre RS - 2nd Mercosur Visual Arts Biennial, Fundação Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul

1999 - Porto Alegre RS - Picasso, Cubism and Latin America, MARGS

1999 - São Paulo SP - The Female Figure in the MAB Collection, MAB/FAAP

1999 - São Paulo SP - A Brazilian Like Me, Like Who?, FAAP

1999 - São Paulo SP - Everyday/Art. Consumption, Itaú Cultural

1999 - São Paulo SP - Brazil in the Century of Art, Galeria de Arte do Sesi

1999 - São Paulo SP - Works on Paper: From Modernism to Abstraction, Dan Galeria

1999 - São Paulo SP - On Paper, Graphite and Ink, Espaço Cultural Banco Cidade

2000 - Brasília DF - Brazil-Europe Exhibition: Encounters in the 20th Century, Conjunto Cultural da Caixa

2000 - Caracas (Venezuela) - Common Territory, Diverse Views: Latin American Artists in the 20th Century, Espacios Unión

2000 - Lisbon (Portugal) - Brazil-Brasils: Remarkable and Astonishing Things. Modernist Perspectives, Museu do Chiado

2000 - Lisbon (Portugal) - 20th Century: Art from Brazil, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Centro de Arte Moderna José de Azeredo Perdigão

2000 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - When Brazil Was Modern: Visual Arts in Rio de Janeiro 1905–1960, Paço Imperial

2000 - São Paulo SP - The Female Figure in the MAB Collection, MAB/FAAP

2000 - São Paulo SP - The Human Figure in the Itaú Collection, Itaú Cultural

2000 - São Paulo SP - Brazil + 500 Exhibition of Rediscovery: Modern Art, Fundação Bienal

2000 - São Paulo SP - Brazil on Paper: Hues and Experiences, Espaço de Artes Unicid

2000 - São Paulo SP - São Paulo: From Village to Metropolis, Galeria Masp Prestes Maia

2000 - São Paulo SP - A Certain Point of View: Pietro Maria Bardi 100 Years, Pinacoteca do Estado

2000 - Valencia (Spain) - From Anthropophagy to Brasília: Brazil 1920–1950, IVAM, Centre Julio Gonzáles

2001 - New York (USA) - Brazil: bodysoul, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

2001 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Modern Collections: Hecilda and Sergio Fadel at Chácara do Céu, Museus Castro Maya, Museu da Chácara do Céu

2001 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Surrealism, CCBB

2001 - São Paulo SP - 30 Masters of Painting in Brazil, MASP

2001 - São Paulo SP - Museum of Brazilian Art: 40 Years, Museu de Arte Brasileira

2001 - São Paulo SP - The Trajectory of Light in Brazilian Art, Itaú Cultural

2002 - Brasília DF - JK: An Aesthetic Adventure, Conjunto Cultural da Caixa

2002 - Niterói RJ - Brazilian Art on Paper: 19th and 20th Centuries, Solar do Jambeiro

2002 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Archipelagos: The Plural Universe of MAM, MAM/RJ

2002 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Brazilian Art in the Fadel Collection: From Modernist Restlessness to the Autonomy of Language, CCBB

2002 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Identities: The Brazilian Portrait in the Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, MAM/RJ

2002 - São Paulo SP - 22 and the Idea of the Modern, MAC/SP

2002 - São Paulo SP - Brazilian Art in the Fadel Collection: From Modernist Restlessness to the Autonomy of Language, CCBB

2002 - São Paulo SP - From Anthropophagy to Brasília: Brazil 1920–1950, MAB/SP

2002 - São Paulo SP - Wild Mirror: Modern Art in Brazil in the First Half of the 20th Century, Nemirovsky Collection, MAM/SP

2002 - São Paulo SP - Image and Identity: A Look at History in the Museu de Belas Artes Collection, Instituto Cultural Banco Santos

2002 - São Paulo SP - Modernism: From the Week of 1922 to Sérgio Milliet’s Art Section, CCSP

2002 - São Paulo SP - In the Time of the Modernists: D. Olivia Penteado, the Lady of the Arts, Museu de Arte Brasileira

2002 - São Paulo SP - Caixa Treasures: Exhibition of Caixa’s Art Collection, Conjunto Cultural da Caixa

2002 - São Paulo SP - Tarsila do Amaral and Di Cavalcanti: Myth and Reality in Brazilian Modernism, MAM/SP

2003 - Belém PA - 22nd Arte Pará Salon, Museu de Arte do Paraná

2003 - Brasília DF - Brazilian Art in the Fadel Collection: From Modernist Restlessness to the Autonomy of Language, CCBB

2003 - Ribeirão Preto SP - 1920s: Emerging Modernity, Museu de Arte de Ribeirão Preto Pedro Manuel-Gismondi

2003 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Autonomy of Drawing, MAM/RJ

2003 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Caixa Treasures: Brazilian Modern Art in Caixa’s Collection, Conjunto Cultural da Caixa

2003 - São Paulo SP - Art and Society: A Controversial Relationship, Itaú Cultural

2003 - São Paulo SP - ArtKnowledge: 70 Years USP, MAC/USP

2003 - São Paulo SP - MAC USP 40 Years: Contemporary Interfaces, MAC/IUSP

2003 - São Paulo SP - Novecento Sudamericano: Artistic Relations between Italy, Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo

2003 - São Paulo SP - Portraits, MAB/SP

2003 - São Paulo SP - Tomie Ohtake in the Spiritual Fabric of Brazilian Art, Instituto Tomie Ohtake

2004 - Brasília DF - JK’s Modernist Gaze, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Palácio do Itamaraty

2004 - Curitiba PR - Tomie Ohtake in the Spiritual Fabric of Brazilian Art, Museu Oscar Niemeyer

2004 - Kyoto (Japan) - Brazil: body nostalgia, National Museum of Modern Art

2004 - Madrid (Spain) - ARCO/2004, Parque Ferial Juan Carlos I

2004 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - The Iconic Face of Brazilian Art, MAM/RJ

2004 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - The Century of a Brazilian: Roberto Marinho Collection, Paço Imperial

2004 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Tomie Ohtake in the Spiritual Fabric of Brazilian Art, MNBA

2004 - São Paulo SP - The Biennials: A Look at Brazilian Production 1951–2002, Galeria Bergamin

2004 - São Paulo SP - Paper Cabinet, CCSP

2004 - São Paulo SP - Masters of Modernism, Estação Pinacoteca

2004 - São Paulo SP - Women Painters, Pinacoteca do Estado

2004 - São Paulo SP - New Acquisitions: 1995–2003, Museu de Arte Brasileira - FAAP

2004 - São Paulo SP - The Price of Seduction: From Corset to Silicone, Itaú Cultural

2004 - São Paulo SP - São Paulo 450 Years Platform, MAC/USP

2004 - Tokyo (Japan) - Brazil: body nostalgia, The National Museum of Modern Art

2005 - São Paulo SP - Faces of Mário, IEB/USP

2005 - São Paulo SP - The Century of a Brazilian: Roberto Marinho Collection, MAM/USP

2005 - São Paulo SP - 100 Years of the Pinacoteca: Formation of a Collection, Galeria de Arte do Sesi

2005 - Fortaleza CE - Brazilian Art in Public and Private Collections in Ceará, Espaço Cultural Unifor

2005 - Paris (France) - Tarsila do Amaral: The Birth of Modernism in Brazil, Maison de l’Amérique Latine

2006 - São Paulo SP - Tarsila do Amaral at BM&F: Affective Path - 120 Years Since Birth, Espaço Cultural BM&F

2006 - São Paulo SP - At the Same Time Our Time, Museu de Arte Moderna

2006 - São Paulo SP - MAM at Oca, Oca

2006 - São Paulo SP - Radical Maneuvers, Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil

2006 - São Paulo SP - JK’s Modernist Gaze, MAB-FAAP

2006 - São Paulo SP - Sérgio Milliet and the Biennials, Centro Cultural São Paulo, Visual Arts Division

2006 - São Paulo SP - A Century of Brazilian Art: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, Pinacoteca do Estado

2006 - São Paulo SP - Viva Culture Viva the Brazilian People, Museu Afro Brasil

2006 - Belém PA - Traces and Transitions of Brazilian Contemporary Art, Espaço Cultural Casa das Onze Janelas

2006 - Florianópolis SC - Traces from the Caixa Collection, Museu de Arte de Santa Catarina

2006 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - A Century of Brazilian Art: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, Museu de Arte Moderna

2007 - São Paulo SP - Art-Anthropology, MAC/USP

2007 - São Paulo SP - Mirada: Latin Americans from MAC USP at the Memorial, Galeria Marta Traba

2007 - Curitiba PR - A Century of Brazilian Art: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, Museu Oscar Niemeyer

2007 - Salvador BA - A Century of Brazilian Art: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection, Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia

2008 - São Paulo SP - Brazilian Brazil, Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil

2008 - São Paulo SP - Bonds of the Gaze, Instituto Tomie Ohtake

2008 - São Paulo SP - MAM 60, Oca

2008 - Buenos Aires (Argentina) - Traveling Tarsila, Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

2008 - São Paulo SP - Traveling Tarsila, Pinacoteca do Estado

2009 - São Paulo SP - Art in France 1860–1960: Realism, Museu de Arte de São Paulo

2009 - São Paulo SP - Fernand Léger: Brazilian Relationships and Friendships, Pinacoteca do Estado

2009 - São Paulo SP - Memorial Revisited: 20 Years, Galeria Marta Traba

2009 - São Paulo SP - Nudes, Galeria Fortes Vilaça

2009 - São Paulo SP - The Critic’s Gaze: ABCA Awarded Art and the Artistic Collection of the Palaces, Palácio dos Bandeirantes

2009 - São Paulo SP - Papers in Focus: 20th Century Masters, Dan Galeria

2009 - São Paulo SP - Treasures of the Roberto Marinho Collection, Espaço Cultural BM&F Bovespa

2009 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Brazilian Brazil, Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil

2009 - São Paulo SP - Under a Tropical Sky, James Lisboa Escritório de Arte

2009 - Madrid (Spain) - Tarsila do Amaral, Fundación Juan March

2009 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Works on Paper, Mercedes Viegas Escritório de Arte

2010 - São Paulo SP - Brazilianness and Modernism, Dan Galeria

2010 - São Paulo SP - Revealed Memories, Museu de Arte Brasileira

2010 - São Paulo SP - Pure Mixtures, Pavilhão das Culturas Brasileiras

2010 - São Paulo SP - Versions of Modernism, Instituto de Arte Contemporânea

2010 - Ribeirão Preto SP - Animal, Galeria de Arte Marcelo Guarnieri

2010 - Rio de Janeiro RJ - Genealogies of the Contemporary, Museu de Arte Moderna

2010 - São Paulo SP - 6th SP-Arte, Fundação Bienal

2010 - Vitória ES - Tarsila on Paper, Museu de Arte do Espírito Santo

2011 - São Paulo SP - Modernisms in Brazil, MAC/USP

2011 - São Paulo SP - Brazilian Papers: The Art of Printmaking - MASP Collection, Museu de Arte de São Paulo

2011 - São Paulo SP - Collection Cutouts, Galeria Ricardo Camargo

2011 - Belo Horizonte MG - 1911–2011: Brazilian Art and Beyond, Itaú Collection, Fundação Clóvis Salgado, Palácio das Artes

2011 - Brasília DF - Women: Artists and Brazilian, Palácio do Planalto

2011 - São Paulo SP - 7th SP-Arte, Fundação Bienal

2011 - Campos do Jordão SP - Art and Culture in the Paraíba Valley, Palácio Boa Vista

2011 - Nova Lima MG - Tarsila and the Brazil of the Modernists, Casa Fiat de Cultura

2012 - São Paulo SP - From the Art Section to the Acquisition Prize: The Genesis of the Drawing Cabinet, Gabinete do Desenho

2012 - São Paulo SP - The Return of the Tamagni Collection: Even the Stars Through Difficult Paths, Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo

2012 - São Paulo SP - Affective Journey, CCBB

2013 - São Paulo SP - Experience ] and [ Transformation, Museu de Arte Brasileira - FAAP

2013 - Campinas SP - 100 Years of Paulista Art in the Pinacoteca do Estado Collection, CPFL Cultura Art Gallery

Bibliography

AMARAL, Aracy. Tarsila: Her Work and Her Time. 3rd ed., rev. and expanded. São Paulo: Edusp; Editora 34, 2003. 512 p., b&w ill.

AMARAL, Tarsila do. Tarsila as Chronicler. Edited by Aracy Amaral. São Paulo: Edusp, 2001. 241 p.

AMARAL, Tarsila do. Tarsila do Amaral. São Paulo: Finambrás, 1998. 225 p., color ill. (Mercosur Artists Cultural Project).

ANDRADE, Mário de; AMARAL, Tarsila do. Correspondence between Mário de Andrade & Tarsila do Amaral. Edited by Aracy Amaral. São Paulo: Edusp; IEB, 2001. 237 p., b&w ill., 18 x 25 cm. (Correspondence of Mário de Andrade, vol. 2).

ARTE in Brazil. Introduction by Pietro Maria Bardi and Pedro Manuel. São Paulo: Abril Cultural, 1979.

BIEZUS, Ladi (ed.). 5 Brazilian Masters: Constructivist Painters – Tarsila, Volpi, Dacosta, Ferrari, Valentim. Translation by Judith Hodgson. Rio de Janeiro: Kosmos, 1977. 175 p., b&w and color ill.

BRAZIL Europe: 20th Century Encounters. Introduction by Francisco Knopli, Alain Rouquié. Brasília: Conjunto Cultural da Caixa, 2000. 79 p., color ill.

CHIARELLI, Tadeu. Brazilian International Art. São Paulo: Lemos, 1999. 311 p., color ill.

GOTLIB, Nádia Battella. Tarsila do Amaral: The Modernist. São Paulo: Senac, 1998. 216 p., color ill.

LEITE, José Roberto Teixeira. 500 Years of Brazilian Painting. Produced by Raul Luis Mendes Silva, Eduardo Mace; design Alessandra Gerin; soundtrack Roberto Araújo. [S.l.]: Log On Informática, 1999. 1 CD-ROM.

LEITE, José Roberto Teixeira. Modern Brazilian Painting. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 1978. 162 p., b&w and color ill.

PEDROSA, Mário. Modern Art Week. In: ______. Academics and Moderns: Selected Texts III. Edited by Otília Beatriz Fiori Arantes. São Paulo: Edusp, 1998. 429 p., b&w ill.

PONTUAL, Roberto. Contemporary Brazilian Art: Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection. Introduction by Pereira Carneiro; translated by Florence Eleanor Irvin and John Knox. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Jornal do Brasil, 1976. 478 p., color ill.

PONTUAL, Roberto. Between Two Centuries: 20th-Century Brazilian Art in the Gilberto Chateaubriand Collection. Preface by Gilberto Chateaubriand; introduction by M. F. do Nascimento Brito. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Jornal do Brasil, 1987. 585 p., color ill.

SCHWARZ, Roberto. The Cart, the Tram, and the Modernist Poet. In: ______. What Time Is It? Essays. São Paulo: Rio, 1987. 180 p.

SESI (ed.). Tarsila, the 1920s. Translated by Yara Nagelschmidt and Ann Puntch. São Paulo: Página Viva, 1997. 157 p., color ill.

SPANUDIS, Theon. Brazilian Constructivists. São Paulo: Ed. do Autor, [19]. 19 p.

Tarsila. Edited by Marcos Antonio Marcondes. São Paulo: Art, 1991. 24 p., b&w ill. (Great Brazilian Artists).

ZANINI, Walter (ed.). General History of Art in Brazil. Introduction by Walther Moreira Salles. São Paulo: Instituto Walther Moreira Salles, Fundação Djalma Guimarães, 1983.

ZILIO, Carlos. The Brazil Question: The Identity of Brazilian Art – The Work of Tarsila, Di Cavalcanti, and Portinari: 1922–1945. 2nd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Relume Dumará, 1997. 139 p., b&w and color ill.

[1] “Pau-brasil”; Oswald de Andrade, 1925.

In: “Tarsila: sua obra e seu tempo”; Aracy Amaral – Co-edition: Editora 34/EDUSP, São Paulo, 2003.

[2] “A Querela do Brasil; a questão da identidade da arte brasileira”; Carlos Zilio; Relume-Dumará; RJ, 1997.

[3] “Tarsila: sua obra e seu tempo”; Aracy A. Amaral – Co-edition: Editora 34/Edusp, São Paulo, 2003. This is the most important critical essay on Tarsila and a classic study on Modernism, first published in 1975 after approximately ten years of research. Aracy Amaral reconstructs, across more than 500 pages, the artist’s biographical trajectory, highlighting the 1920s and the Pau-Brasil and Anthropophagy movements. A monumental work!

Aracy tells us: “When we dedicate ourselves to research on an artist or a theme, we inevitably become somewhat ‘hostage’ to the subject at hand. That was the case over the past thirty years, during which I wrote numerous texts on the artist for symposia and catalogs, as well as organized exhibitions of her work.”

[4] “Tarsila; The 1920s”; Sônia Salzstein et al.; SESI Art Gallery; São Paulo, 1997.

[5] At 16, she painted a copy of a “Sacred Heart of Jesus,” recently auctioned by “James Lisboa, Art Office.”

Read more at www.tarsiladoamaral.com.br

[6] Pedro Alexandrino Borges (SP, 1856-1942) was a Brazilian painter, draftsman, decorator, and teacher. He was a disciple of Almeida Júnior in São Paulo, after attending the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, where he studied drawing with José Maria de Medeiros and painting with Zeferino da Costa. In 1897, he traveled to Paris, where he stayed for nine years. Back in Brazil, he held a solo exhibition with 110 paintings, 84 of them still lifes, the genre for which he became renowned. He was also a private teacher to some modernists, including Tarsila do Amaral, Anita Malfatti, and Aldo Bonadei.

[7] João de Sousa Lima (São Paulo, 1898-1982) was a distinguished Brazilian pianist, composer, conductor, and teacher. He began piano studies with his brother, José Augusto, and later with Luigi Chiaffarelli, who considered him very talented and offered him free lessons. Through a friend, he was introduced to Dr. José Estanislau do Amaral, father of painter Tarsila do Amaral, whose home he began frequenting. He also attended the residence of Senator José de Freitas Valle, called Villa Kyrial, an important center of São Paulo’s cultural life. Thanks to his friendship with the Senator, who also presided over the “Commission of the Artistic Boarding School of the State of São Paulo,” he received a scholarship and lived in Paris during approximately 1922-1935.

[8] The 1924 São Paulo Revolt, also called the 'Forgotten Revolution,' "Isidoro’s Revolution," "Revolution of 1924," and "Second 5th of July," was the second Tenentist uprising and the largest armed conflict ever to occur in São Paulo. Led by retired General Isidoro Dias Lopes, it involved several lieutenants, including Joaquim do Nascimento Fernandes Távora (who died in the revolt), Juarez Távora, Miguel Costa, Eduardo Gomes, Índio do Brasil, and João Cabanas.

Launched in São Paulo on July 5, 1924 (the second anniversary of the 18 Fort of Copacabana Revolt, the first Tenentist uprising), the revolt occupied the city for 23 days, forcing the state president, Carlos de Campos, to flee to the interior after the Campos Elíseos Palace, the government seat at the time, was bombarded.

In the state’s interior, rebellions occurred in various cities, with city halls being taken over.

The insurgents contacted the state vice-president, Colonel Fernando Prestes de Albuquerque, in Itapetininga, inviting him to assume the revolutionary government in São Paulo. Colonel Prestes, who had already organized a battalion in defense of legality along the Sorocabana Railway region, responded to the insurgents...

[9] The father obtained the annulment of the first marriage in 1925.

[10] Abaporu is an oil painting on canvas by Brazilian painter Tarsila do Amaral. Today, it is the most valuable Brazilian painting worldwide, having reached a price of US$1.5 million, paid by Argentine collector Eduardo Costantini in 1995.

It is displayed at the Latin American Art Museum of Buenos Aires (MALBA). Abaporu derives from the Tupi terms aba (man), pora (people), and ú (to eat), meaning “man who eats people.” The name references Modernist Anthropophagy, which sought to digest foreign culture and adapt it to Brazil. Painted in 1928 as a birthday gift for the writer Oswald de Andrade, her husband at the time, Tarsila emphasized manual labor (large feet and hands) and downplayed intellectual work (small head), reflecting the era’s valuation of physical effort.

[11] Oswald de Andrade satirized in his works the Brazilian elite’s submission to developed countries. He proposed the “cultural devouring of imported techniques to rework them autonomously, converting them into exportable products.”

Combining Brazilian primitivism with a form of primitivism inherited from Breton (with Marxist leanings) through a Freudian psychoanalytic lens, Oswald deepened his thought in this direction.

In maturity, Oswald sought philosophical grounding for Anthropophagy, linking it to Nietzsche, Engels, Bachofen, Briffault, and other authors, even writing theses on the subject, such as The Decline of Messianic Philosophy.

[12] “Coffee Growing in the 1929 Crisis and the Revolution”; Lúcia Helena Storto and Sidney Aguilar Filho. Sources: H. Schlittler Silva; A. Villanova Vilela and W. Suzigan, cited by Paul Singer. "Brazil in the Context of International Capitalism." In Boris Fausto. (General History of Brazilian Civilization, 2nd ed., São Paulo, Difel, 1977, vol. 8, p.355)

[13] The 1932 Constitutional Revolution, Revolution of 1932, or Paulista War, was an armed movement in São Paulo, Brazil, between July and October 1932—covering all of São Paulo state, southern Mato Grosso (now Mato Grosso do Sul), Minas Gerais, and Rio Grande do Sul—aiming to overthrow the Provisional Government of Getúlio Vargas and promulgate a new constitution for Brazil.

It was São Paulo’s response to the 1930 Revolution, which had ended the autonomy states enjoyed under the 1891 Constitution.

The 1930 Revolution prevented the inauguration of the former state president (now governor) of São Paulo, Júlio Prestes, to the presidency, overthrowing President Washington Luís, ending the Old Republic, invalidating the 1891 Constitution, and establishing the Provisional Government led by Getúlio Vargas, who had lost the 1930 election.

Law 2.430, June 20, 2011, inscribed the names of Martins, Miragaia, Dráusio, and Camargo—the MMDC—São Paulo heroes of the 1932 Constitutional Revolution, in the Book of National Heroes.

It was the first major revolt against Getúlio Vargas’ government and the last large-scale armed conflict in Brazil.

In total, there were 87 days of combat (July 9 to October 4, 1932—the last two days after the Paulista surrender), with an official death toll of 934, though unofficial estimates report up to 2,200 fatalities, and numerous interior cities of São Paulo suffered damage due to fighting.

After the 1932 revolution, São Paulo returned to being governed by Paulistas, and two years later, a new constitution—the 1934 Constitution—was enacted.

[14] Luis Martins (Rio de Janeiro 1910 - São Paulo 1981) was a Brazilian writer, journalist, critic, memoirist, and poet. In 1928, he wrote his first novel. Later, he published "Lapa" in 1936, which was seized by the police. This event influenced his move to São Paulo in 1938, as well as his long and tumultuous romantic relationship with Tarsila do Amaral. When introduced, he was 26 and she 47. Before settling in São Paulo, Luís Martins debuted as an art critic, publishing "Modern Painting in Brazil" in 1937. In 1941, he began writing as an art critic for Diário de S. Paulo. As a critic, he aligned with the lineage of Mário de Andrade, Sérgio Milliet, and Geraldo Ferraz. He won the 1965 Jabuti Prize in the "Biography and/or Memoirs" category for "Noturno da Lapa," and later the same prize in the Fiction category in 1972 for "A Girafa de Vidro." He was a columnist for O Estado de São Paulo for 36 years, signing as L.M. He died in an accident while traveling from São Paulo to Rio de Janeiro in 1981.

[15] Aracy Abreu Amaral, São Paulo, February 22, 1930, is an art critic and curator. Full professor of Art History at the School of Architecture and Urbanism at USP, she was also director of the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo (1975-1979), the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (1982-1986), and a member of the International Award Committee of the Prince Claus Fund, The Hague, Netherlands.

Historian, critic, and curator, she graduated in Journalism from PUC-SP (1959), completed her Master’s in Philosophy (1969) and Doctorate in Arts at USP. Her Habilitation (1983) and Full Professorship exams were conducted at the School of Architecture and Urbanism at USP (1988).

Awards: She received the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship and, in 2006, the Fundação Bunge Prize (formerly Moinho Santista Prize) for her contributions to Museology. In addition to organizing numerous important exhibitions, she coordinated the "Rumos" project at Itaú Cultural (2005-2006) and curated the 8th Mercosur Biennial and the Chile Triennial.